Heritage

The Story of the Pearl Tepeluk

Among the newspapers published in Serbia at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, Mali žurnal stood out for its focus on fashion. On January 7, 1896, it published a story titled The Pearl Tepeluk. Behind the seemingly traditional title lies, as the editorial board put it, nothing less than a crime story, in which a humble telegraphist named Dragi embezzles state funds and ends up in prison – all that to buy a pearl tepeluk for his wife. The couple previously had the following conversation:

– “I’ll buy you a diamond ring for one hundred dinars, but then we have to save if we don’t want to get into debt”.

– “But I don’t want a ring; I want a tepeluk, just like a lawyer’s wife”. – “All right, darling, but I’m a telegraph operator and I can’t pay 60 ducats for a tepeluk. A lawyer earns that much, if not more, from an ordinary litigation. This is no big deal for them. So, you could do with a ring, and besides the wedding ring, you also have earrings and necklaces. You’re not naked and bare as a shorn sheep” – Dragi proceeded humorously.

After a short pause, she shook her head and yelled: “And I’m not a sheep after all… I want a tepeluk, no matter what. Is that clear”?

The content of the story and its publication in Mali žurnal testify to the fashionable and symbolic significance that the headgear known as the pearl tepeluk held in Serbian women’s attire in the past. French Slavist Louis Léger noted in 1873 that he saw women in Serbia wearing tepeluks adorned with pearls valued at a hundred ducats, and that tepeluks were passed down from a mother’s wardrobe to a daughter’s dowry as treasured family heirlooms.

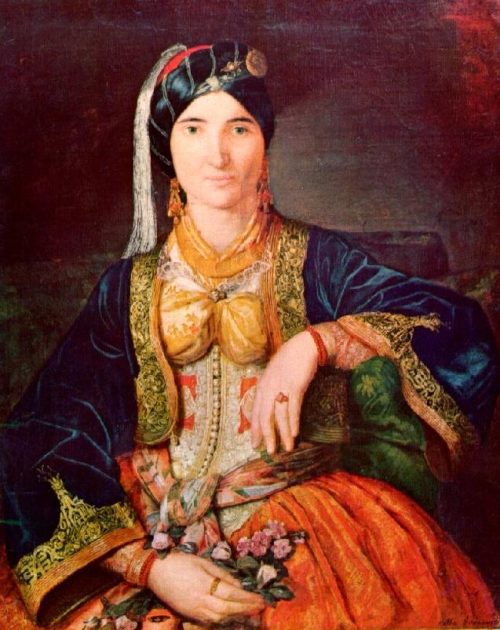

The pearl tepeluk emerged in women’s fashion in 19th-century Serbia as part of the national costume, which, after Serbia gained autonomy in 1830, spontaneously evolved through the selection and modification of elements from the former Ottoman-Balkan dress inventory. In the 1830s and 1840s, women’s national costume was accompanied by a shallow red fez with a long tassel of silk, gold, or silver threads, which fell over the right ear. Instead of a tassel, the fez could be decorated with a string of coins arranged in a spiral on a circular fabric base, or with a round metal plate embellished with motifs reflecting local artistic styles, often made of silver, gilded, or in the filigree technique. This decoration was also called a tepeluk, and in simpler versions, the fez was adorned with cord embroidery.

By the mid-19th century, the pearl tepeluk became an essential part of the national costume. It was a shallow cap made of red cloth, similar to a fez, embroidered with pearls arranged in cones whereby smaller cones formed concentric circles around a larger central cone. Around the tepeluk, as with the fez, women wrapped braids and bareš, a twisted scarf or ribbon made of plain or patterned fabric. The braids and bareš were initially adorned with coins and jewelry such as diamond brooches and rings. Unmarried girls wore a simple velvet or silk ribbon as the bareš, while married women wore velvet ribbons embroidered with floral embroidery of pearls.

By the late 1840s, modern diamond jewelry in the shape of flowers and floral branches, imported from Europe, largely replaced coin jewelry, which had been rooted in the Ottoman-Balkan tradition. Such jewelry was especially prominent in the headgear of Princess Persida Karađorđević’s rich national costume. The large and luxurious diamond branches adorning her bareš reminded contemporaries of a diamond diadem. Influenced by European customs and fashion, the black tepeluk, embroidered with black beads, emerged in the last decades of the 19th century. Worn during mourning periods, it was paired with appropriately colored garments and a simple black bareš, without jewelry.

Together with the libade – a short, front-opening jacket with wide sleeves, the pearl tepeluk remained a part of bourgeois self-presentation even into the first half of the 20th century. Worn with European-style clothing, this fashion item played a key role in the visual expression of social status and national identity.

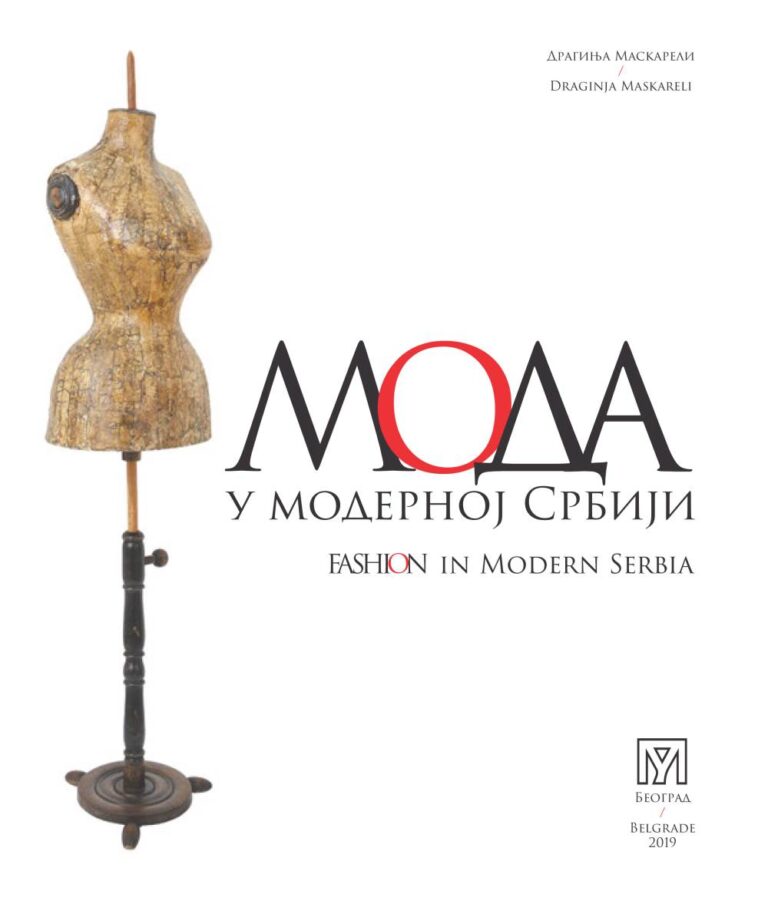

Draginja Maskareli

Museum advisor – Art and Fashion Historian

Dictionary of less known terms:

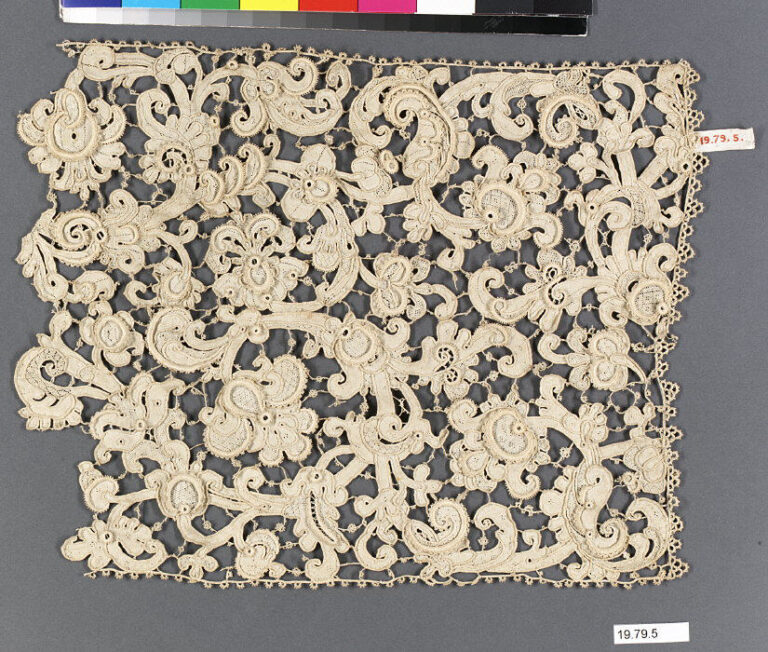

Openwork – a term used in the history of visual culture for techniques that produce decoration by openings in solid materials such as metal, wood, stone, pottery, ivory, leather, or cloth.

Passementerie – the art of making trimmings or edgings, buttons, tassels, fringes, etc.

Pearl tepeluk and bareš with matching jewelry, second half of the 19th century; collection presentation of the Museum of Applied Art in Belgrade, 15 July 2025; photo: D. Maskareli

Katarina Ivanović, Belgrader M. J., 1846–1847; National Museum of Serbia; photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Uroš Knežević, Princess Persida Karađorđević, before 1855, lithographed by Gabriel Decker in Vienna; photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Uroš Knežević, Young woman in a Serbian national costume, around 1856; National Museum of Serbia; photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Steva Todorović, Woman in a Serbian national costume, 1861; National Museum in Niš; photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Blog

Flowers in Fashion

Due to their appealing visual appearance and complex symbolism, flowers

Reading in/on Fashion

Reading is always in fashion. Likewise, numerous luxury and paperback

Art history as fashion inspiration

As visual artists, fashion designers have often drawn inspiration from

Lace in fashion

Lace is an openwork fabric with motifs tied by a

Mothers, fashion, and other stories

An interesting fashion exhibition titled M&Others, dedicated to the complex theme

Summer, Art and Fashion

For a long time, summer has been an inspiration both

Medal-worthy style: a brief history of Olympic fashion

From July 26 to August 11, 2024, Paris, one of

Fashion, Identity, and Culture of Living in Belgrade in the 19th and Early 20th Century: Religious Holidays and Balls

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, religious holidays were

Fashion, Identity, and Lifestyle in Belgrade in the 19th and Early 20th Century: Gatherings, Sports, Recreation, and Excursions

Social life in Belgrade developed intensely during the 19th century.

Women’s Urban Dress and National Costume in Serbia in the 19th Century

During the first decades of the 19th century, the appearance

Clothing and Rulers’ Representation: Prince Miloš Obrenović

In different areas and different cultures, clothes have been used

How did the women’s handbag become an important fashion accessory?

From the earliest times, handbags have been a useful addition

Fashion Icons of the Past: Queen Maria

Even during her upbringing, Queen Maria, as a member of

Fashion Icons of the Past: Queen Natalija

Serbian Queen Natalija had a deep interest in fashion. Although

History of Fashion and Street Style

In 1994, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London hosted

Story of Cashmere

When we mention cashmere, elegance and luxury are among the

Kashmir Shawls: Luxury and Status

Since the second half of the 17th century, the Levant

The Magic of Wool

Wool, a fiber obtained from sheep’s fleece, possesses numerous characteristics

Belgrade Tailors and the Timeless Elegance of Men’s Suits

The French Revolution swept away from the European fashion scene

Fashion in modern Serbia

In the history of European fashion, the mid-19th century marks