Since the second half of the 17th century, the Levant has been the main route through which printed cotton fabrics from India reached Europe. Cities such as Venice, Genova, Livorno, and Marseille began to develop local production that imitated the imported Indian textiles. The intricate patterns and vibrant colors made these fabrics attractive to both European and Ottoman buyers, paving the way for the fashion of Kashmir shawls.

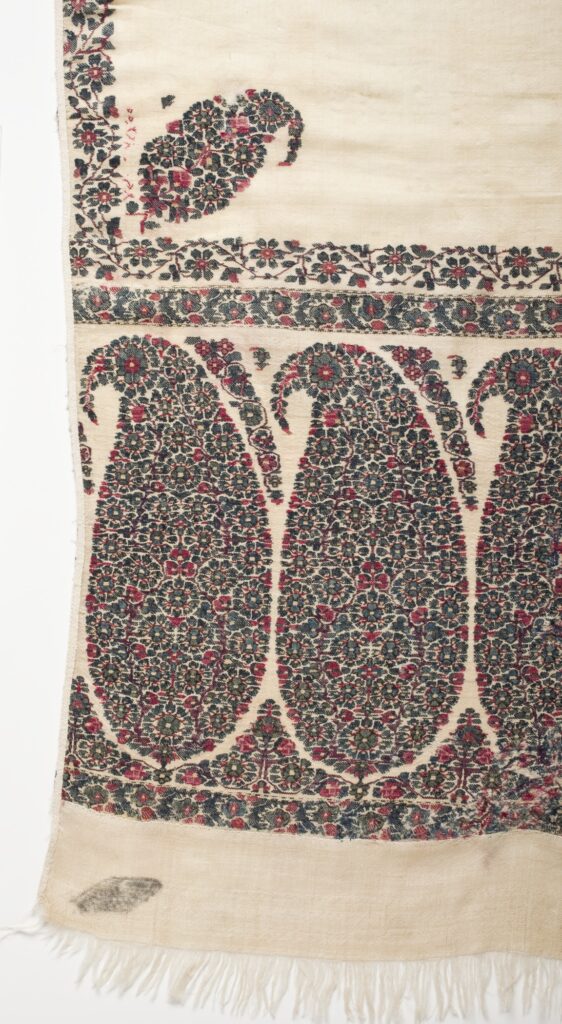

Kashmir shawls originate from the region of Kashmir in northwest India. They are handmade from fine Kashmiri wool, known as pashmina, and often adorned with the distinctive tear-shaped motif with a curled tip. Their import into modern Europe began in the late 18th century and became a luxurious status symbol and fashion item in the early 19th century. Shawls inspired by Kashmiri designs started to be produced in France and England. The highest-quality European shawls were made in Lyon, while Paisley in Scotland became known for cheaper imitations.

Kashmir shawls, especially those of large dimensions, also had a practical purpose: they were worn as comfortable wraps over the oversized dresses of the mid-19th century, known as crinolines. From the 1870s, as dress dimensions decreased, Kashmir shawls slowly went out of fashion and were often repurposed, used as material for making coats, jackets, dresses, and other clothing items.

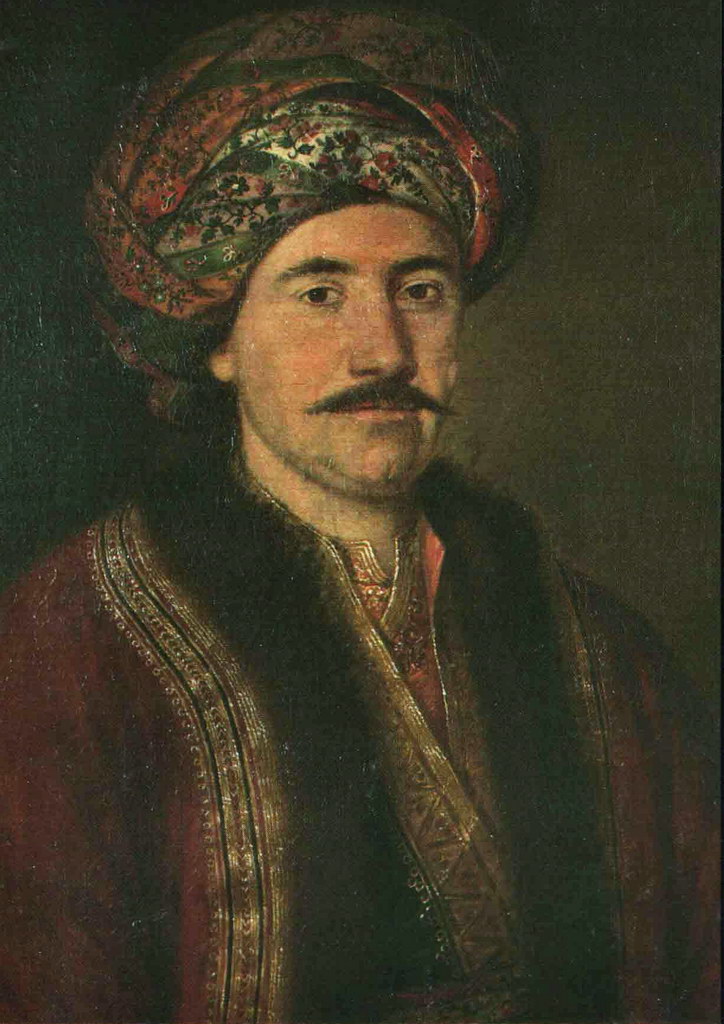

Fashion history had long been centered on Western Europe, perceiving the fashion of Kashmir shawls exclusively in this part of the world. However, these shawls, along with other luxury fabrics, reached trading routes to Istanbul, Alexandria, Russia, and the Balkans, finding their place in different fashion systems. Wealthy Christians in the Ottoman Empire wore expensive shawls with striped and floral patterns around their heads, known as “çalma.” Two portraits painted by the artist Pavel Đurković, one of the Wallachian boyar Constantin Cantacuzino from around 1820 and one of Serbian Prince Miloš Obrenović from 1824, are well-known examples of the use of çalma for visual representation.

These head coverings, resembling turbans, defied strict Ottoman laws requiring differentiation in clothing between Muslims and non-Muslims, so Turks reluctantly viewed Christians wearing çalma. Belgrade Turk Rašid-bej recorded that during the reading of a decree, the Belgrade pasha ordered that a fine Kashmir shawl with stripes and floral patterns be brought, and then one of the finest Kashmir shawls was tied around Prince Miloš’s head, while other Serbian leaders were given one each. The event caused dissatisfaction among the present Turks, who, upon seeing what had been done, left the assembly and returned to their homes.

In Serbia, before the issuance of the Hatt-i Sharif in 1830 and the acquisition of autonomy, wearing a shawl around the head was considered the epitome of male elegance. One of the reasons for this was undoubtedly the fact that wearing shawls signified a certain degree of freedom. People’s deputy Sava Ljotić wrote from Istanbul in 1819 that the people of Serbia were criticized for carrying weapons and wearing shawls, to which Prince Miloš replied that the people did not commit any evil with their weapons but carried them to defend themselves against criminals and troublemakers, while wearing shawls was a way to show off and display the freedom bestowed upon us by the Sultan.

In the documents of the time in Serbia, luxury shawls were most commonly referred to as “lahor-šal,” which indicates another important center of shawl production, the Pakistani city of Lahore. As part of the wedding gifts for his nieces Jelka and Simka, the daughters of Jevrem Obrenović, Prince Miloš ordered at least six Lahore shawls from Istanbul in 1833. It is also recorded that in 1824, when his daughter Petrija got married, he intended to give two Lahore shawls as gifts to the groom’s sisters. Considering the value of these shawls, the pragmatic prince ordered that on this occasion, Princess Ljubica should part with her shawl, but if she was reluctant to do so, she should find another one, while the second shawl could be given to Đorđe Popović Ćeleš’s wife.

Draginja Maskareli

Museum Advisor – Art and Fashion Historian

- William Simpson, “Producers of Shawls in Kashmir,” 1867, chromolithograph; photo: Wikimedia Commons / public domain

- Fashion of Kashmir Shawls in Paris, fashion illustration, Journal des dames et des modes, Paris, March 26, 1809; photo: Wikimedia Commons / public domain

- Detail of a Kashmir Shawl, circa 1810, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA); photo: Wikimedia Commons / public domain

- Pavel Đurković, Wallachian Boyar Constantin Cantacuzino, circa 1820; photo: Wikimedia Commons / public domain

- Pavel Đurković, Prince Miloš with a “turban,” 1824, National Museum of Serbia; photo: Wikimedia Commons / public domain