Fashion stands today as one of the most widespread means of visual expression in a culture. This notion was underscored as far back as 1886 by the Swiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin, who postulated that the design of a shoe could be as significant an indicator of the value of medieval art as the grand Gothic cathedrals of Western Europe. Although Wölfflin primarily aimed to emphasize the role of everyday objects in shaping a holistic cultural image of a society and era, the connection between fashion and medieval art has persisted through diverse manifestations.

During the 19th century, a national idea prevailed in Europe, prompting its advocates to seek inspiration from the past, particularly from the medieval period, to create authentic national cultural models. Modern, Parisian fashion often bore the brunt of their critique. Nevertheless, this inclination towards medieval influence also impacted contemporary fashion trends. By the late 19th century, purses made of metal mesh emerged in fashion, their appearance evoking, among other things, the armor of medieval knights. These mesh purses, which have been preserved in significant numbers within the legacies of Serbian bourgeois families, frequently featured frames shaped as recognizable elements of Gothic architecture – pointed arches or quatrefoils. These accessories remained stylish even between the two World Wars, crafted from silver, as well as various silver-plated metals and alloys.

Inspired by European proponents of the national idea, the Association of Serbian Youth, founded in 1847 in Belgrade, sought to break away from German attire and adopt a Serbian national costume that would be (re)constructed by studying medieval models. The result of these clothing reform endeavors was the dušanka, a male jacket named after Emperor Dušan, intended to emphasize national identity and a connection to a glorious past. In reality, the dušanka was a hussar-style jacket, borrowed from the European wardrobe, akin to what could be seen in portrayals of scenes and personalities from Serbian history in 18th-century Vojvodina paintings.

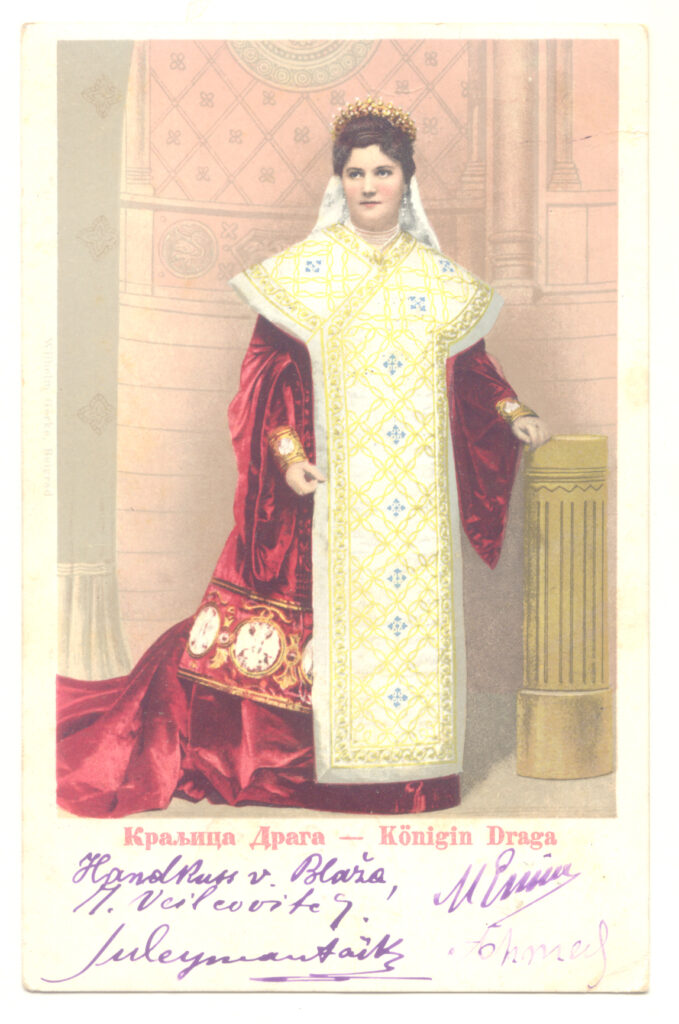

Queen Draga Obrenović, in her effort to promote the image of being the first Serbian queen after Princess Milica, commissioned the creation of a special court costume inspired by medieval aristocratic attire. Designed by architect Vladislav Titelbah, the costume was crafted at the Women’s Workers’ School and adorned with embroidery from the workshop of Svetislav J. Kostić. The official photographs of the queen from 1902 bear witness to its appearance.

The notion of constructing a national costume based on medieval models also resonated in Serbian painting. The pursuit of an authentic national costume that would give Serbian saints, national heroes, and historical figures an appropriate national character played a significant role in the development of national art. It is known that for this purpose, the painter Dimitrije Avramović traveled and visited old Serbian monasteries, exploring evidence of medieval clothing in historical heritage.

The timeless splendor of regal and aristocratic robes of mosaic from monastery frescoes did not fade even during the era of socialist Yugoslavia. As such, the inspiration drawn from medieval art held a significant place in the work of Aleksandar Joksimović, a prominent Serbian and Yugoslav fashion designer. In March 1967, Joksimović presented the high fashion collection Simonida at a fashion show in the Gallery of Frescoes in Belgrade. This collection drew inspiration from the name and epoch of the medieval Serbian queen Simonida. This event held great importance for Yugoslav fashion, as the collection garnered acceptance and emulation by younger generations and garment manufacturers – something unprecedented in a socialist country. That same year, at the International Festival of Fashion in Moscow, where representatives from both the Eastern and Western political blocs performed together for the first time, Simonida was acclaimed as the most successful collection.

At the exhibition of Yugoslav industry and art in Paris in 1969, Joksimović unveiled the high fashion collection Prokleta Jerina, also inspired by the local history of the medieval era, named after Despotess Jerina Branković. The models showcased were acclaimed during this event in the fashion capital as marvelously contemporary and international. Renowned fashion houses Pierre Cardin and Dior expressed particular respect for this collection. During that era, high fashion, which had been instrumental in shaping fashion trends since the mid-19th century, evolved into an elite institution tailored to individuals with the most discerning aesthetic demands and members of the wealthiest social strata.

Draginja Maskareli

Museum advisor – Art and Fashion Historian

1. Purse made of metal mesh, late 19th – early 20th century; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 2.0 / Joe Haupt

2. Queen Draga in court costume, 1902; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0 /Museum of. Rudnik and Takovo Region

3. Queen Simonida, fresco from the Gračanica monastery; around 1320, photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

4. Aleksandar Joksimović and models in dresses from the Simonida collection, 1967; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 / Museum of Applied Art in Belgrade

5. The image of despotess Jerina Branković from the Esphigmenou Charter, 1429; photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain