Fashion Print and Fashion Trends

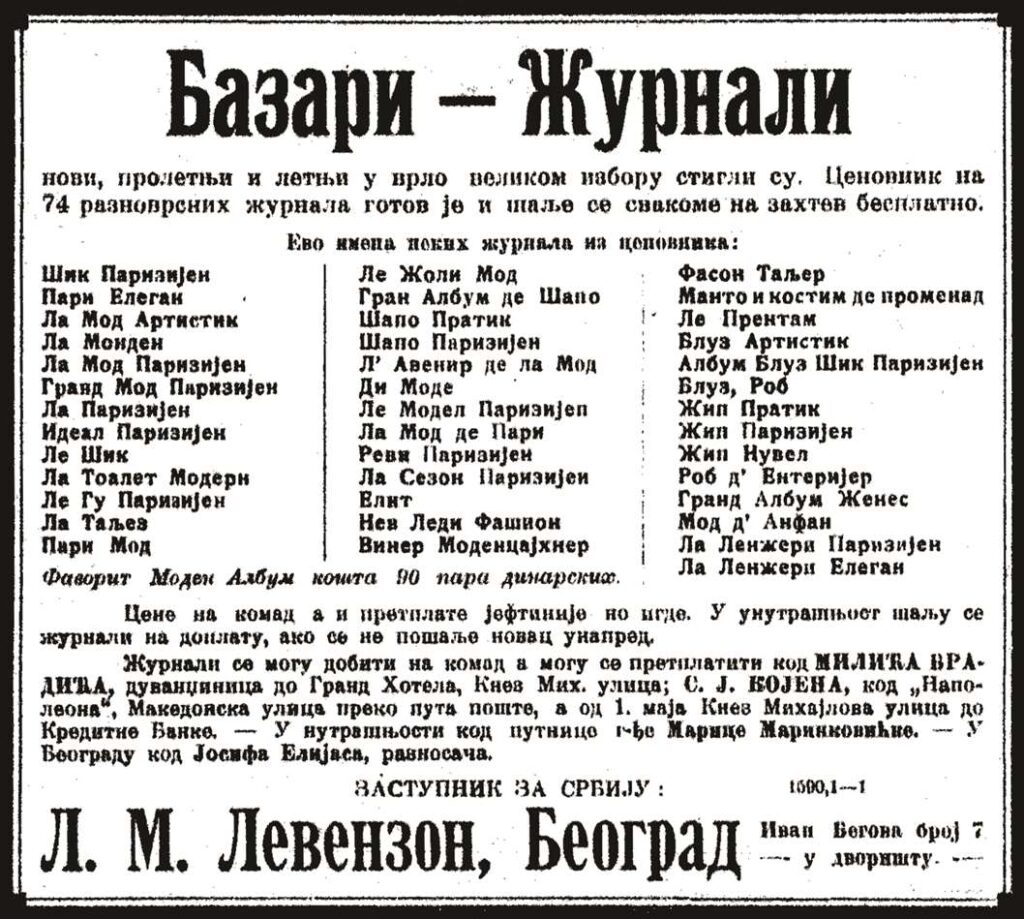

During the last decades of the 19th century, various family and fashion magazines were accessible to the citizens of Serbia, sometimes in individual households, and to a greater extent at social gatherings and tailor shops. Starting from the beginning of the 20th century, the offer of foreign fashion magazines could also be tracked through advertisements in print media. In 1909, the Geca Kon’s bookstore in Belgrade, through advertisements in the Politika newspapers, offered its readers 18 different French, German, and Viennese fashion magazines, including Die Modenwelt, Grosse Modenwelt, Der Bazar, Wiener Mode, Elegante Mode, Ilustrierte Frauenzeitung, La Mode Parisien, and others. Additionally, in 1912, L. M. Levenzon advertised himself as the representative for Serbia for as many as 74 imported fashion magazines. At that time, Mali žurnal (The Small Journal) stood out among the magazines with fashion themes in Serbia. It even had a special edition with the title Pariska moda (Parisian Fashion), dedicated exclusively to fashion and published in 1902. Unfortunately, already in 1903, Mali žurnal announced that Pariska moda had to cease publication because the expenditures were enormous, as well as that there was a widespread interest […] in reviving this fashion magazine, and many ladies, old and young, promised to become permanent subscribers, as opposed to what they had done before, when there were 50 readers per single subscription. The emergence of fashion magazines in Europe can be traced back to the 17th century. The French ruler Louis XIV, known as the Sun King, viewed fashion as a means to dominate European culture and actively encouraged the French fashion industry. His finance minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, famously stated that fashion was to France what Peruvian gold mines were to Spain. In France, from 1672 to 1832, one of the oldest fashion magazines, Le Mercure galant, was published. It was founded and edited by writer and historian Jean Donneau de Visé. During the time of the French Revolution, which temporarily disrupted the flow of French fashion, Germany also emerged as a publishing center for fashion magazines. The oldest German fashion magazine, Journal des Luxus und der Moden, was published in Weimar from 1786 to 1826, with Friedrich Justin Bertuch as the first publisher. Naturally, fashion in France soon reestablished its dominance, and the publication of fashion magazines continued. The fashion magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, with Professor Pierre de La Mesangère as the first editor, was published in Paris from 1797 to 1839. One of the publications that continued the German tradition of producing high-quality fashion magazines in the 19th century was Die Modenwelt: die Illustrierte Zeitung für Toilette und Handarbeiten (World of Fashion: An Illustrated Magazine for Fashions and Fancy-work). Founded by Franz von Lipperheide in Berlin in 1865, this magazine quickly achieved great success, being published in various countries in as many as 14 languages. It boasted the highest circulation among fashion magazines of that time and was even sold in Brazil. In the pages of Die Modenwelt, a magazine well-read in Serbia, fashion illustrations accompanied by pattern sheets were published. This facilitated ordering clothеs in the latest fashion from skilled local craftsmen. Examples of fashion illustrations and pattern sheets from Die Modenwelt are preserved today in the Museum of Applied Art in Belgrade and the City Museum Subotica. A significant leap in the history of fashion print was made by publisher Lucien Vogel when he began publishing Gazette du bon ton in Paris in 1912. This highly influential fashion magazine continued to be published even after World War I. Viewing fashion as a representative form of visual art, Vogel engaged a group of young artists to create illustrations for the new magazine, many of whom were educated at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, including Paul Iribe and George Barbier. In modern Europe and Serbia, fashion print played a crucial role in conveying information about contemporary fashion trends. Holding a prominent place among various books, magazines, and newspapers, whose expanded production marked the development of European society from the 18th century onward, fashion print contributed to the formation of civil society and the public sphere, emphasizing the significance of fashion in shaping bourgeois visual identity. Draginja MaskareliMuseum advisor – Art and Fashion Historian 1. Advertisement of the Geca Kon’s bookshop for foreign fashion magazines, Politika, Belgrade, March 8, 1909. 2. Advertisement by L. M. Levenzon for imported fashion magazines, Politika, Belgrade, April 13, 1912.3. Front page of the magazine Pariska moda, Belgrade, July 14, 1902.4. Front page of Die Modenwelt, 1911, photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public domain5. Georges Barbier, illustration for the Gazette du bon ton, 1914; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC0 1.0/ Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Middle Ages as Inspiration in Serbian Fashion

Fashion stands today as one of the most widespread means of visual expression in a culture. This notion was underscored as far back as 1886 by the Swiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin, who postulated that the design of a shoe could be as significant an indicator of the value of medieval art as the grand Gothic cathedrals of Western Europe. Although Wölfflin primarily aimed to emphasize the role of everyday objects in shaping a holistic cultural image of a society and era, the connection between fashion and medieval art has persisted through diverse manifestations. During the 19th century, a national idea prevailed in Europe, prompting its advocates to seek inspiration from the past, particularly from the medieval period, to create authentic national cultural models. Modern, Parisian fashion often bore the brunt of their critique. Nevertheless, this inclination towards medieval influence also impacted contemporary fashion trends. By the late 19th century, purses made of metal mesh emerged in fashion, their appearance evoking, among other things, the armor of medieval knights. These mesh purses, which have been preserved in significant numbers within the legacies of Serbian bourgeois families, frequently featured frames shaped as recognizable elements of Gothic architecture – pointed arches or quatrefoils. These accessories remained stylish even between the two World Wars, crafted from silver, as well as various silver-plated metals and alloys. Inspired by European proponents of the national idea, the Association of Serbian Youth, founded in 1847 in Belgrade, sought to break away from German attire and adopt a Serbian national costume that would be (re)constructed by studying medieval models. The result of these clothing reform endeavors was the dušanka, a male jacket named after Emperor Dušan, intended to emphasize national identity and a connection to a glorious past. In reality, the dušanka was a hussar-style jacket, borrowed from the European wardrobe, akin to what could be seen in portrayals of scenes and personalities from Serbian history in 18th-century Vojvodina paintings. Queen Draga Obrenović, in her effort to promote the image of being the first Serbian queen after Princess Milica, commissioned the creation of a special court costume inspired by medieval aristocratic attire. Designed by architect Vladislav Titelbah, the costume was crafted at the Women’s Workers’ School and adorned with embroidery from the workshop of Svetislav J. Kostić. The official photographs of the queen from 1902 bear witness to its appearance. The notion of constructing a national costume based on medieval models also resonated in Serbian painting. The pursuit of an authentic national costume that would give Serbian saints, national heroes, and historical figures an appropriate national character played a significant role in the development of national art. It is known that for this purpose, the painter Dimitrije Avramović traveled and visited old Serbian monasteries, exploring evidence of medieval clothing in historical heritage. The timeless splendor of regal and aristocratic robes of mosaic from monastery frescoes did not fade even during the era of socialist Yugoslavia. As such, the inspiration drawn from medieval art held a significant place in the work of Aleksandar Joksimović, a prominent Serbian and Yugoslav fashion designer. In March 1967, Joksimović presented the high fashion collection Simonida at a fashion show in the Gallery of Frescoes in Belgrade. This collection drew inspiration from the name and epoch of the medieval Serbian queen Simonida. This event held great importance for Yugoslav fashion, as the collection garnered acceptance and emulation by younger generations and garment manufacturers – something unprecedented in a socialist country. That same year, at the International Festival of Fashion in Moscow, where representatives from both the Eastern and Western political blocs performed together for the first time, Simonida was acclaimed as the most successful collection. At the exhibition of Yugoslav industry and art in Paris in 1969, Joksimović unveiled the high fashion collection Prokleta Jerina, also inspired by the local history of the medieval era, named after Despotess Jerina Branković. The models showcased were acclaimed during this event in the fashion capital as marvelously contemporary and international. Renowned fashion houses Pierre Cardin and Dior expressed particular respect for this collection. During that era, high fashion, which had been instrumental in shaping fashion trends since the mid-19th century, evolved into an elite institution tailored to individuals with the most discerning aesthetic demands and members of the wealthiest social strata. Draginja MaskareliMuseum advisor – Art and Fashion Historian 1. Purse made of metal mesh, late 19th – early 20th century; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 2.0 / Joe Haupt 2. Queen Draga in court costume, 1902; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0 /Museum of. Rudnik and Takovo Region 3. Queen Simonida, fresco from the Gračanica monastery; around 1320, photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain 4. Aleksandar Joksimović and models in dresses from the Simonida collection, 1967; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 / Museum of Applied Art in Belgrade 5. The image of despotess Jerina Branković from the Esphigmenou Charter, 1429; photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain