In the 19th and early 20th centuries, religious holidays were an important segment of social life and identity in Belgrade. The celebration of religious holidays was an important event in the family, so the house was thoroughly cleaned before each holiday, and numerous traditional dishes and cakes were prepared.

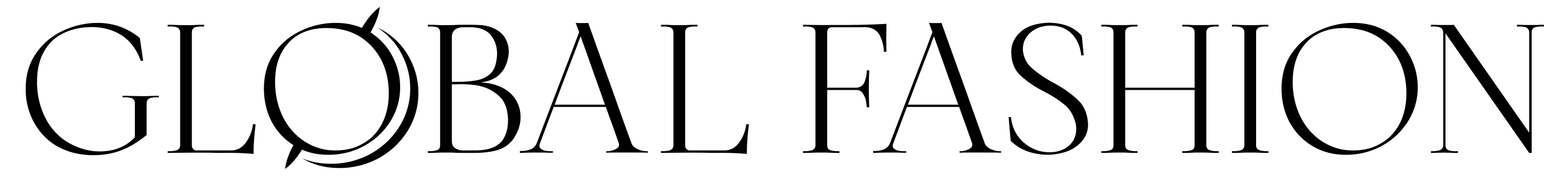

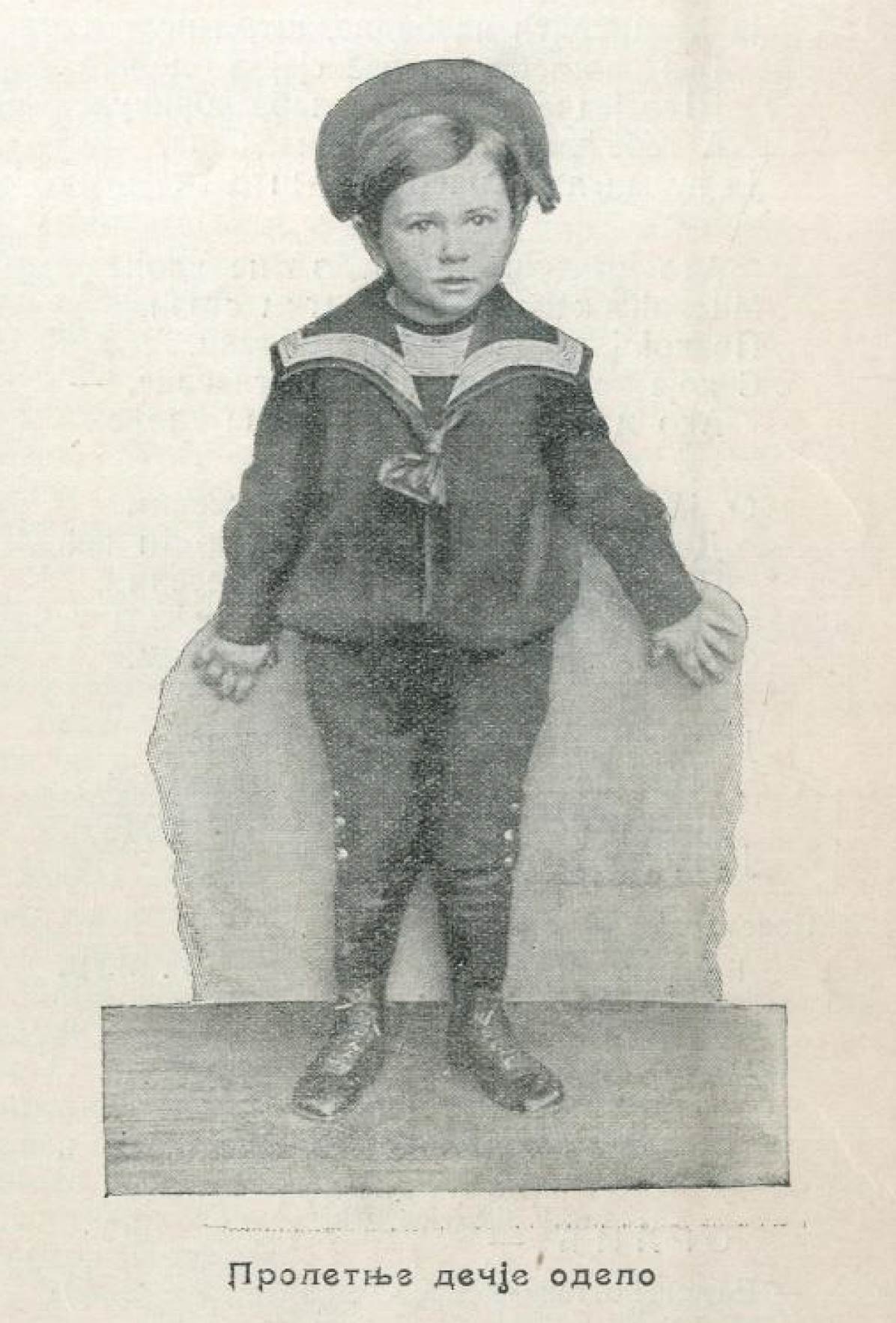

Serbian slava is one of the elements included in the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Slava, as a solemn celebration of the family’s patron saint, besides the religious one, also had a strong social component, which included the exchange of visits. On days of great feasts, such as St. Nicholas, on the streets of Belgrade, solemnly dressed married couples could be seen, who visited the acquaintances on foot or by carriage. Men wore a black suit, black coat, hat, or top hat, while women wore visiting dresses, usually of darker colors, with some discreet jewelry and a mandatory hat. The drawing of the Austro-Hungarian travel writer Felix Kanitz from 1859 represents the slava of a Belgrade family. Members of the family, dressed in national costume, are shown welcoming guests in an interior the appearance of which is fully harmonized with the cultural model of bourgeois Europe. Although the European fashion influence has prevailed in Belgrade since the middle of the 19th century, the national costume, as clothing with appropriate symbolism, was still worn at slavas and other special occasions.

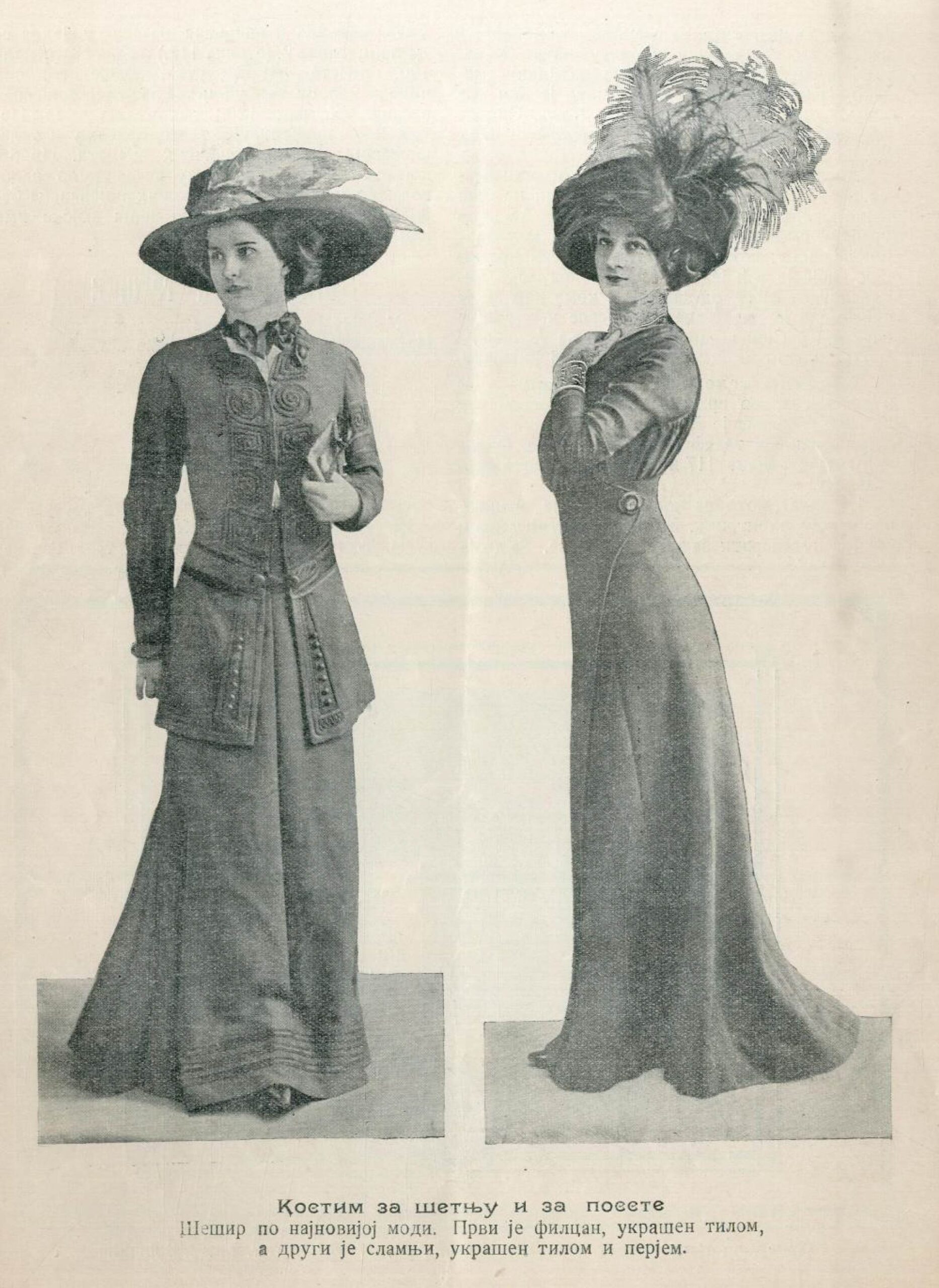

Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, and Easter were celebrated mostly in the family circle. The people only went to church or to visit the elders and greet them. Lawyer and politician Kosta Hristić notes in his memoirs that on Good Friday, a solemn ritual of bringing out the Epitaphios is performed in all churches, while it is especially solemn in the Cathedral. A special place in the children’s calendar of holidays was occupied by Lazarus Saturday or Vrbica, which was also an occasion to buy children new festive clothes for the holiday procession. On that occasion, girls wore silk dresses, hats, and patent leather shoes, while boys wore popular sailor suits and sailor caps. Hristić also remembers small merchants who decorate their windows with whole wreaths of small Vrbica bells, children’s caps, dresses, and straw hats, but also the big ones, with fashionable goods in new styles, felt and Panama hats, all of the latest form and color.

During the ball season, which lasted from December to the end of March or the beginning of April, numerous balls were held in Belgrade. The balls were organized by different associations, including the Women’s Society, Officer Corps of the Belgrade Garrison, Belgrade Singing Society, Belgrade Shooting Society, Craft Association, Belgrade Trade Youth, and Belgrade Workers’ Society. Balls were often held in the Civil Casina, which was founded in 1869 and located in the Main Bazaar, at the corner of today’s Kralja Petra and Kneza Mihaila streets. The establishment had great importance for the development of social life in Belgrade. In addition to balls, there were also held concerts, speeches, parties, and art exhibitions, while the Civil Casina reading room had a well-stocked library, and regularly received local and foreign newspapers and magazines.

The most solemn were the court balls attended by high-ranking military figures, politicians, diplomats, and distinguished merchants with their families. Kosta Hristić left a written testimony about one of the balls held by Prince Mihailo and Princess Julija. This ball was attended by guests from all levels of society: merchants in European or “Turkish” dress, women in Serbian dress with caps – tepeluks, belts – bajaders tassels, and necklaces of pearls and ducats, young women and girls in broad crinolines, but also people in Turkish and Austrian uniforms, such as the Belgrade pasha and senior Austrian officers from Zemun and Pančevo.

Court balls were particularly glamorous in the 1880s, during the duration of the marriage of King Milan Obrenović and Queen Natalija, as well as during Natalija’s stay in Serbia as Queen Mother in the mid-1890s. At court balls, in addition to the ball dress, the national costume often appeared as a dress code for women. Particularly popular were the so-called costume balls where, instead of ball dresses, various folk and exotic costumes were worn.

Draginja Maskareli

Museum advisor – Art and Fashion Historian

Dictionary of less known terms:

Epitaphios – a religious textile with embroidered or painted images showing the body of Christ immediately after being taken down from the cross

Tepeluk (tr. tepelik) – a shallow women’s cap made of red cloth and decorated with pearl embroidery, worn as a part of Serbian national costume

Bajader – a long and wide patterned silk sash with fringes, worn as a part of Serbian national costume

Slava-celebrating family, Belgrade, 1859; source: Kanic, F. (1989), Srbija : zemlja i stanovništvo od rimskog doba do kraja XIX veka, prva knjiga, Beograd, Srpska književna zadruga.

Walking and visiting dress; Nedelja, Belgrade, 21 February 1910

Spring children’s dress; Nedelja, Belgrade, 7 February 1910

Walking dress for grown-up girls; Nedelja, Belgrade, 14 February 1910

Modern ball dress and newest spring dress, style “Directoire”; Nedelja, Belgrade, 21 February 1910