In different areas and different cultures, clothes have been used for centuries as a means of expressing social status. In the 19th century, during the dynamic period of building a modern state, according to social and political circumstances, as well as the models of Ottoman and European rulers’ representation, clothes were successfully and prudently used by the Serbian uprising leader and prince Miloš Obrenović.

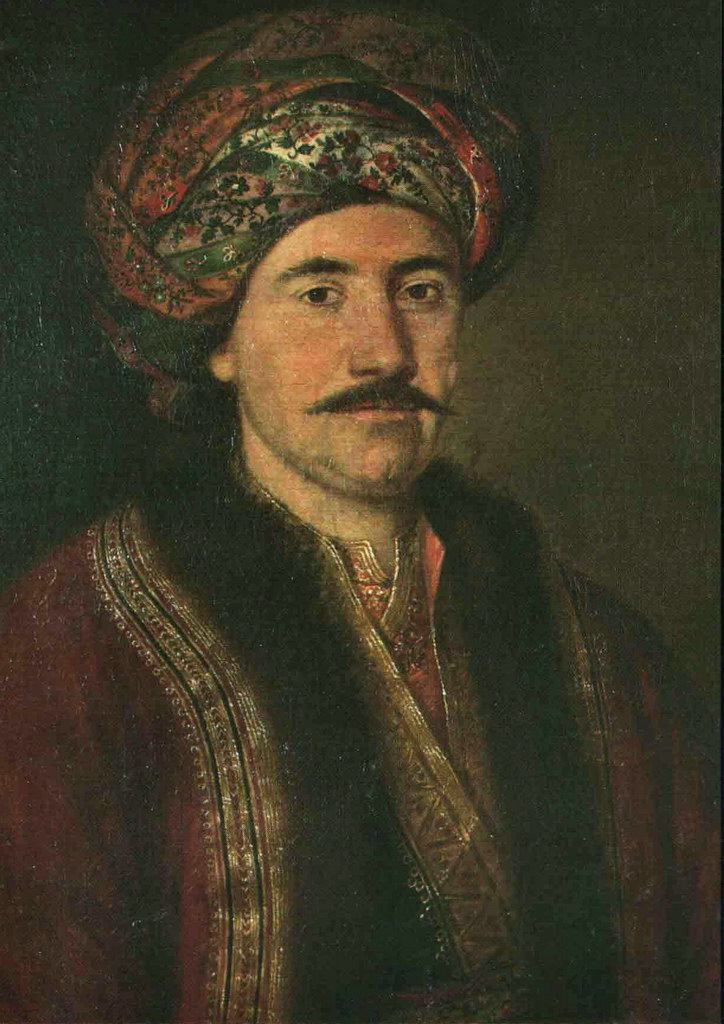

After the end of the Second Serbian Uprising in 1817, Prince Miloš, in a Turkish dress with a çalma on his head and yemeni on his feet, looked more like a wealthy saraf or merchant than a political representative of the Serbian people, writes historian Mihailo Gavrilović. We see this way of dressing in one of the prince’s canonical portraits, which is known as Prince Miloš with a turban. This portrait, today in the National Museum of Serbia, was painted in 1824 in Kragujevac by Pavel Đurković. At that time, a Kashmir shawl with a distinctive striped and floral pattern, wrapped around the head like a turban, together with a red upper dress whose edges are trimmed with fur and embroidered with metal thread, was a typical element of the luxurious clothing of wealthy Christians in the Ottoman Balkans that expressed their desire to equate their status with the ruling classes through visual code. In the same year, Đurković painted two more portraits of the prince, in which he is shown in a simpler, folk dress, with a fez on his head.

In a Turkish dress, Prince Miloš attended the great public ceremony of reading Hatt-i sharif and berat, which was held in Belgrade, on Tašmajdan, in 1830. Since Sultan Mahmud II with these documents granted autonomy to the Principality of Serbia and declared Miloš the hereditary prince, the prince adapted his clothes to the new situation. In the period after 1830, the most common representational dress of Prince Miloš was a dolman made of red cloth, decorated with embroidery with metal thread and cords, with which he wore a kalpak made of fur with an aigrette. Photographer and lithographer Anastas Jovanović noted that the prince said that the Serbs were dressed like that during the old times. During the first reign of Prince Miloš, Novine srpske in their reports also marked this dress as an old Serbian dress.

The complete look of the dress can be seen on several preserved portraits of Prince Miloš, among which is the one from the collection of the National Museum of Serbia, the work of Moritz Daffinger from around 1848. Also, Prince Miloš’s sumptuous red dolman is preserved in the collection of the Historical Museum of Serbia, along with about sixty other clothing items that belonged to members of the Obrenović dynasty. The fact that it is sewn by the high standards of men’s tailoring certainly contributes to the representational quality of Miloš’s dolman. Historian Radoš Ljušić states that at the wedding of Prince Mihailo in Vienna in 1853, the old prince attracted significantly more attention than the younger prince and that he made his way through the huge mass of the curious Viennese world, dressed in a luxurious and rich Serbian dress, like some old Serbian knight.

Old Serbian dress – dolman was worn by the prince on various solemn occasions. One of them was the ceremony of awarding the Great Order of Sultan Mahmud II (Nişan-ı Zişan), which was held in Bregovo on Timok in 1834. Novine srpske reported that the prince was dressed in a Russian uniform during the bestowing of the order, which showed his respect and devotion to the Russian emperor as the patron of Serbia, but also to the Russian court and its institutions. The next day, when he visited Vizier Hussein Pasha, who had previously ceremoniously presented him with the order, he was dressed in an old cherry-colored Serbian dress, with a sable kalpak on his head. The Russian uniform, which is mentioned in the report from Bregovo, represents another important model of Prince Miloš’s clothing in the period after the acquisition of autonomy in 1830. By wearing a black military jacket with general epaulette and rank on the collar and cuffs according to the Russian model, the prince emphasized his position and autonomy of Serbia in relation to the supreme Ottoman authority. In the Russian uniform, also worn by his brothers Jovan and Jevrem, he is shown in the portrait of Uroš Knežević from 1835, preserved in the collection of the Historical Museum of Serbia.

Draginja Maskareli

Museum advisor – Art and Fashion Historian

Dictionary of less known terms:

- Çalma (Turkish: çelme) – a decorative fabric wrapped around the fez or head

- Yemeni (Turkish: yemeni) – light and shallow leather shoes

- Saraf (Turkish: saraf) – money changer

- Dolman – a type of men’s knee or thigh-length coat, with long and narrow sleeves, decorated with cords

- Kalpak – parade dress military cap made of fur, with a top made of felt or silk

Pavel Djurković, Prince Miloš with a turban, 1824, National Museum of Serbia; photo: Wikimedia Commons / public domain / National Museum of Serbia

Pavel Djurković, Prince Miloš with a fez, 1824, National Museum of Serbia; photo: Wikimedia Commons / public domain / National Museum of Serbia

Moritz Daffinger, Prince Miloš, around 1848, National Museum of Serbia; photo: Wikimedia Commons / public domain / National Museum of Serbia

Anastas Jovanović, Prince Miloš Obrenović, 1852, National Library of Serbia; photo: Wikimedia Commons / public domain / National Library of Serbia

Uroš Knežević, Prince Miloš, 1835–1840, Historical Museum of Serbia; photo: Wikimedia Commons / public domain / Historical Museum of Serbia / user: Sadko