Flowers in Fashion

Due to their appealing visual appearance and complex symbolism, flowers have been incorporated into various forms of dress since the times of ancient civilizations. In ancient Egypt, the lotus motif was often seen on clothing and jewelry. This flower, associated with the Sun god Ra, symbolized rebirth and life after death. In ancient Greece and Rome, floral wreaths adorned the heads of gods, heroes, and brides. Victors were crowned with laurel wreaths, while garlands of roses and myrtle were attributes of the goddesses of love, Aphrodite and Venus. In the Middle Ages, via the Silk Road, fabrics decorated with floral motifs arrived from Asia to Europe and were used to make clothes. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Italian cities as Venice and Florence were renowned for the production of luxury fabrics, while from the 17th century, the French town of Lyon became the center of silk textile production. Patterned silk textiles – velvet and brocade were highly prized, and embroidery techniques were also used for floral decorations. In the 17th and 18th centuries, floral motifs became ubiquitous in both men’s and women’s court fashion across Europe. While men’s clothing in the 17th century was considerably more extravagant, in the 18th century, women’s clothing took the lead in opulence. Women’s dresses were often made of silk brocade adorned with various floral patterns. Among the fashionable dresses of the 18th century was the robe à la française, known for two vertical pleats in the back that fell from the shoulders. These pleats often appeared in clothes depicted in the paintings of Antoine Watteau, so they were later named Watteau pleats. Floral-patterned clothing became accessible to broader social classes with the emergence of chintz – a glazed cotton fabric with printed or painted motifs that gained popularity in Europe in the 17th century. Initially imported from India, chintz began to be produced locally in the 18th century. Renowned centers of chintz production were located in France, England, and Switzerland. Basma, a cotton fabric with printed floral motifs, had an important role in the Balkan dress. During Prince Miloš Obrenović’s visit to Constantinople in 1835, the rooms where the Serbian delegation was accommodated were equipped with carpets and basma-covered ottomans. In the 19th century, basma with various floral designs was frequently used for linings in men’s and women’s Serbian urban dress. In the second half of the 19th century, within the Ottoman cultural sphere, women’s dresses richly decorated with metal thread embroidery depicting floral branches, vases, and flower baskets came into fashion. These dresses, most often made of dark red or dark purple velvet, are historically known by the Turkish name bindalli, meaning thousand branches. They were worn at weddings and other festive occasions and were part of a bride’s dowry. Many bindalli dresses are now kept in museum collections worldwide as part of the traditional attire of various national and religious groups that lived within the former Ottoman Empire, including Serbian women from southern Serbia and from Kosovo and Metohija. A frequent decorative motif on bindalli dresses was the rose. Flowers have remained in fashion throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Floral motifs marked the hippie trends of the 1960s and also could be seen in the wardrobes of celebrities like actress Audrey Hepburn and Princess Diana. Today, they appear in street fashion as well as on clothes of renowned brands such as Valentino, Dolce & Gabbana, and Erdem. In some countries, Floral Design Day is celebrated on February 28. Draginja MaskareliMuseum advisor – Art and Fashion Historian Men’s suit (Scotland, 1745) and dress, robe à la française (USA, 1760–1775); Museum FIT, New York; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0 / user: DanielPenfield Men’s suit, France, c. 1755; LACMA, Los Angeles; photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain Chintz dress, c. 1770–1790; MoMU, Antwerpen; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 / photo: Hugo Maertens, Bruges Dress, bindali, Istanbul, late 19th century; Museum of Applied Art, Belgrade; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 RS / user: Gmihail

Reading in/on Fashion

Reading is always in fashion. Likewise, numerous luxury and paperback publications, with pages dedicated to a wide variety of fashion topics, can be seen in bookstore windows and shelves in Serbia and worldwide. Given that an essential part of summer preparations, besides the careful selection of clothing, also includes compiling a reading list, in this blog, we will highlight several books that, over the past decades, have contributed to the development and understanding of the dress and fashion history in Serbia. The first history of fashion written in the Serbian language was published back in 1964 under the title Odelo i oružje (Dress and Arms). Its author, Pavle Vasić, a painter, art historian, art critic, and university professor, can today be regarded as the founder of fashion studies in Serbia. Vasić’s book was based on the lectures he gave in the History of Costume course at the Faculty of Applied Arts in Belgrade. It was conceived as a textbook for students and covered the dress history of various peoples and cultures, from ancient times to the modern era, concluding with the fashion of the 1950s. The book is richly and systematically illustrated, using a wide range of templates – from public monuments to fashion illustrations and photographs. In addition to Pavle Vasić himself, the illustrations were drawn by painter and archaeologist Rastko Vasić, as well as costume designers Zora Živadinović Davidović and Jovanka Kočoba. The significance of this publication is further confirmed by the fact that it saw two more editions, in 1974 and 1992, supplemented with new information and illustrations. In the second half of the 20th century, in line with global museum trends, fashion began to claim its place in Serbian museums. The exhibition Gradska nošnja u Srbiji tokom XIX i početkom XX veka (Urban Dress in Serbia in the 19th and Early 20th Centuries), curated by Dobrila Stojanović, was held in 1980 at the Museum of Applied Art in Belgrade. On this occasion, Stojanović published a reference study catalogue, where she expertly contextualized fashion in Serbia in the 19th and early 20th centuries within the general history of fashion and European fashion trends. My modest contribution to the further musealization of the topic was the exhibition Fashion in Modern Serbia, held in 2019, also at the Museum of Applied Art. The accompanying catalog essay examined the development of fashion in Serbia through the lens of visual culture studies, emphasizing the pluralism of cultural models. The seminal study by Mirjana Prošić-Dvornić Clothing in Belgrade in the 19th and Early 20th Century, published in 2006, minutely elucidates the various aspects of the process of establishing a European fashion system and its functioning in 19th-century Serbia – from the political, economic and cultural development of the state and society, through the construction of the national costume, to the market placement of fashion products. Among the publications that examined fashion within the realm of material culture, one that stands out is the book by Danijela Velimirović Kible, baklave i fistani (Gables, Baklavas, and Fistans), published in 2021. The book contains an extensive chapter on rural and urban dress among Serbs in the 19th and early 20th centuries, providing a detailed insight into the emergence and development of urban clothing models and fashion, as well as the specificities of dress in rural environments. The cosmopolitan spirit of fashion in interwar Belgrade was revived in 2000 by Bojana Popović in the exhibition Fashion in Belgrade 1918–1941 at the Museum of Applied Art, accompanied by a rich and modernly written catalog. The image of the fashion and cultural milieu of socialist Yugoslavia was presented in 2008 by Danijela Velimirović in the book Aleksandar Joksimović: moda i identitet (Aleksandar Joksimović: Fashion and Identity), which also represents the first monograph on a fashion designer written in our region. Surely, some of these titles (and there are many more), which can be found not only in physical and virtual bookstores and used bookstores, but also in libraries, will make for interesting additions to the reading list of any fashion enthusiast. Familiarizing ourselves with the history of fashion in Serbia not only allows us to understand the past but also enables us, as direct participants in this dynamic fashion story, to continue developing our own fashion style and identity. Draginja Maskareli Museum Advisor – Art and Fashion Historian Vasić, P. (1964), Odelo i oružje [Dress and Arms], Belgrade: Academy of Arts in Belgrade. Stojanović, D. (1980), Gradska nošnja u Srbiji tokom XIX i početkom XX veka [Urban Dress in Serbia in the 19th and Early 20th Centuries], Belgrade: Museum of Applied Art. Popović, B. (2000), Moda u Beogradu 1918–1941 [Fashion in Belgrade 1918–1941], Belgrade: Museum of Applied Art. Prošić-Dvornić, M. (2006), Odevanje u Beogradu u XIX i početkom XX veka [Clothing in Belgrade in the 19th and early 20th century], Belgrade: Stubovi kulture. Velimirović, D. (2008), Aleksandar Joksimović: moda i identitet, Beograd: Utopija. Maskareli, D. (2019), Moda u modernoj Srbiji: Moda u Srbiji u XIX i početkom XX veka iz zbirke Muzeja primenjene umetnosti u Beogradu, Beograd: Muzej primenjene umetnosti.

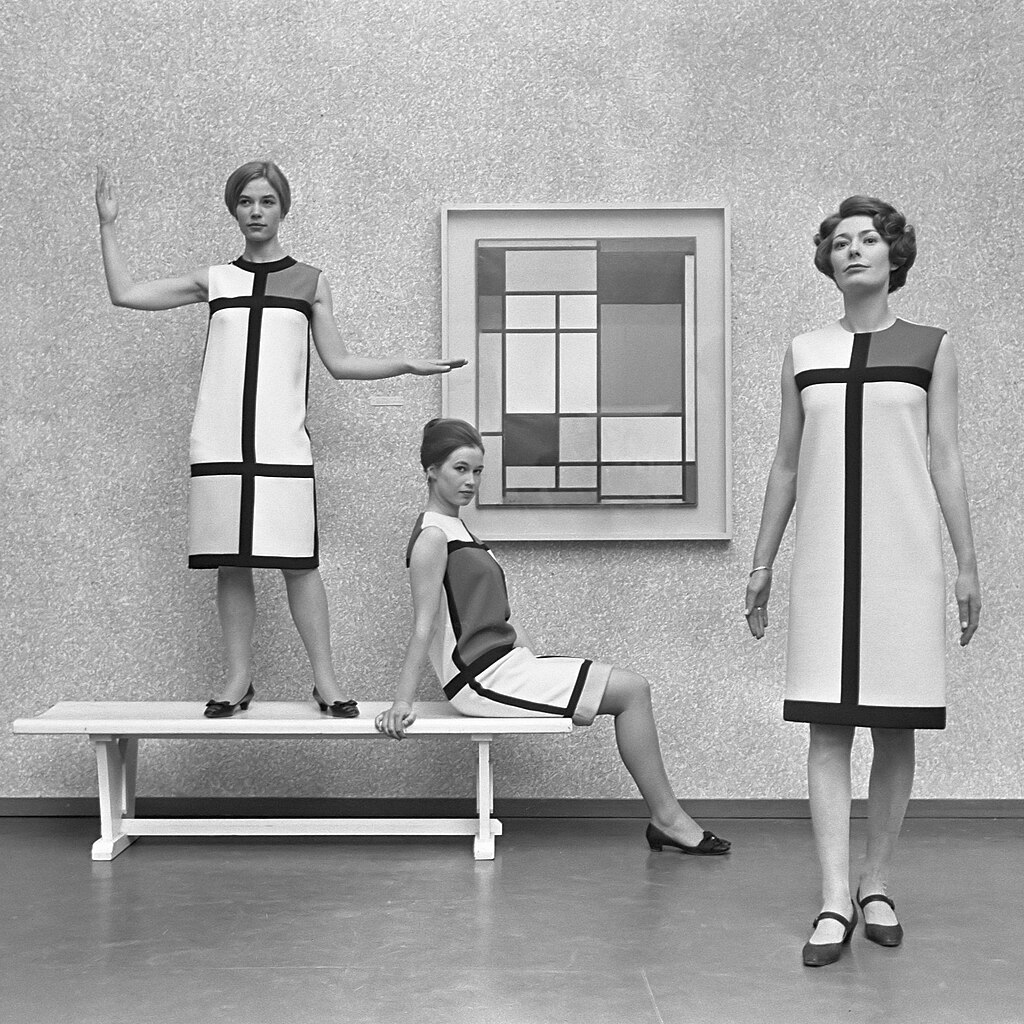

Art history as fashion inspiration

As visual artists, fashion designers have often drawn inspiration from various artistic movements and phenomena. Although Karl Lagerfeld insisted on separating art from fashion, his work, as well as that of many other designers, contains numerous art historical references. One of the most well-known such examples is the Mondrian collection, designed by Yves Saint Laurent in 1965. The collection paid homage to several modern artists, including Serge Poliakoff and Kazimir Malevich. Since the most significant pieces in the collection were six cocktail dresses inspired by the paintings of Piet Mondrian, the entire collection was named Mondrian. The A-line silhouette of the sleeveless dresses, made from wool jersey to hang straight without wrinkling, was characteristic of 1960s fashion. Today, Saint Laurent’s Mondrian dresses are preserved in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The influential fashion designer Madeleine Vionnet was fascinated by Greek culture and art. А product of this fascination was the evening dress Petits chevaux or Vase grècque, created in 1921. The dress is recognizable for the motif of a frieze with rearing horses, which was taken from the clothes of one of the figures depicted on the Pronomos Vase from around 400 BCE. The Greek vase, now held by the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, portrays an antique theater crew with the famous musician Pronomos, in the presence of their patron god, Dionysus. Made of crêpe, a fine and delicate silk fabric, and adorned with metal thread embroidery, the dress became highly popular, so its numerous copies of varying quality have survived until today. An original piece is preserved in the Museum of Decorative Arts (Musée des Arts Décoratifs) in Paris. As a contemporary of renowned Surrealists and Dadaists, Elsa Schiaparelli collaborated with artists such as Salvador Dalí and Jean Cocteau. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London holds an evening coat that Schiaparelli designed in 1937 based on Cocteau’s drawings. Since the double image was a preoccupation of Cocteau and other Surrealists, the decoration in the upper part of the coat’s back can be read both as a vase of roses and two profiles facing each other. The extravagant coat was made from silk jersey, embroidered with metal and silk thread, and decorated with appliquéd silk flowers. Gianni Versace considered the artist Andy Warhol his kindred spirit. In tribute to Warhol and their shared fascination with pop culture, Versace dedicated his Spring/Summer 1991 collection to him. One of the most striking pieces in the collection was an evening dress adorned with prints of Warhol’s 1960s portraits of James Dean and Marilyn Monroe. The collections of Dolce & Gabbana have also frequently been inspired by historical and artistic phenomena. Their Fall 2012 collection evoked the tradition of Sicilian Baroque, incorporating opulent bullion embroidery, lace, and velvet. On the other hand, their Fall 2013 collection Tailored Mosaic was based on motifs from Byzantine-style mosaics from the Monreale Cathedral in Sicily. The renowned Serbian and Yugoslav fashion designer Aleksandar Joksimović also drew inspiration from art history. In March 1967, in a fashion show held at the Gallery of Frescoes in Belgrade, Joksimović presented his haute couture collection Simonida. Born in 1933 in Priština, into an old Serbian merchant family, he found inspiration for the collection in the Gračanica Monastery and the famous fresco from around 1320, depicting the medieval Serbian queen Simonida. The collection had a big impact on contemporary Yugoslav fashion and was frequently copied. Various artistic movements and figures influenced other Joksimović’s collections as well, such as Vitraž (1968), Milena Barilli (1975), and Mozaik (1975). Unfortunately, according to current knowledge, Joksimović’s runway pieces have not been preserved. Draginja MaskareliMuseum advisor – Art and Fashion Historian Yves Saint Laurent, Mondrian dresses, 1966; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC0 1.0 / Nationaal Archief Madeleine Vionnet, Petits chevaux / Vase grècque dress, 1921; Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0 / Jean-Pierre Dalbéra (detail) Pronomos vase, around 400 BCE; National Archaeological Museum, Naples; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0 / ArchaiOptix Dolce & Gabbana, Dress from Tailored Mosaic collection (2013) at the exhibition M&Others, Modemuseum Hasselt, 10 September 2024; photo: D. Maskareli Aleksandar Joksimović with models wearing dresses from Simonida collection, 1967; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 / Museum of Applied Art in Belgrade

Lace in fashion

Lace is an openwork fabric with motifs tied by a mesh structure, originated in Venice and Flanders, no later than the first half of the 16th century. In early modern Europe, as a symbol of luxury and prestige, lace was often the most expensive part of the clothing of a particular wealthy and distinguished person. Until the appearance of machine lace in the 19th century, it was made by hand, and the two basic techniques of its production were bobbin lace, which developed from the art of passementerie, and needle lace, which evolved from embroidery techniques. Well-known lace-making centers were Venice, Brussels, Mechelen, Valenciennes, Bruges, and others. Bobbin lace was made on a lacemaking pillow with a fixed pattern, by interlacing threads wound on bobbins, where the interlaced threads were fixed with pins. Needle lace was made with a needle over a patterned base. It was most often made of linen thread, but after 1800, cotton and less frequently silk and metal thread began to be used for its production. The complex process of making bobbin lace was shown around 1669–1670 by a Dutch painter Jan Vermeer in the painting Lacemaker, which is now in the Louvre Museum in Paris. Although today lace is mostly associated with women’s sensuality, things were a little bit different in the past. In the 17th century, lace was primarily used in men’s clothing to decorate shirts, hems, and collars. This way of using lace in men’s clothing can be seen in preserved visual representations of the French king Louis XIV (1638–1715). Also known as the Sun King, this ruler played an important role in positioning France as a global fashion center. Seeing fashion as a means of dominating European culture, he encouraged the French fashion industry, while his finance minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, is credited with saying that fashion is to France what the Peruvian gold mines are to Spain. In the 18th century, lace gained its place in women’s clothing. On the other hand, men, under the influence of the ideas of rationalism and the Enlightenment, gradually gave up the use of this extravagant detail. Lace also became an important part of women’s private space, in which women draped lace peignoirs or arranged their cosmetics on lace-covered dressing tables. The use of lace in the manufacture of underwear has long remained one of its important purposes. In the 19th century, there were fundamental changes in the character of lace. In addition to the new, bourgeois values of the French Revolution, which influenced the decline in the popularity of lace, industrialization affected many craft sectors, including lacemaking. In Nottingham, in 1809, John Heathcoat patented a machine with a mechanical loom for lace production. Machine lace became available to the wider strata of society, and its producers did not strive to create new and original motifs, but uncritically copied and combined historical patterns. By the end of the 19th century, machine production of lace prevailed although hand production continued until the First World War, when there were significant changes in women’s fashion, which had to adapt to the new, more active position of women in society. At that time, lace was completely marginalized as a fashion detail, which continued during the following decades, when Coco Chanel and Madeleine Vionnet introduced practical women’s clothing, new cuts, and materials. Only after the Second World War, lace came back into fashion with exclusive evening dresses by Christian Dior and Cristóbal Balenciaga. In the late 1980s, and especially during the 1990s, lace experienced its fashion renaissance, when John Galliano and Calvin Klein began to design lace clothing. She kept her place in the production of wedding dresses among which is the iconic wedding dress of Grace Kelly, Princess of Monaco, from 1956, a creation of the American costume designer Helen Rose. References to this dress can be seen in the 2011 wedding dress of the Princess of Wales, Kate Middleton, designed by Sarah Burton, the then creative director of the Alexander McQueen fashion house.Although, according to Czech curator Konstantina Hlaváčková, lace is something old-fashioned, a symbol of femininity with which the majority of women no longer identify, this delicate fabric has been a prominent part of European visual and clothing culture for centuries. Collections of early modern, handmade European lace can be found today in many museums around the world, including the Lace Museum (Museo del Merletto) on the island of Burano near Venice and the Fashion & Lace Museum (Musée Mode & Dentelle) near the Grand-Place in Brussels. Draginja Maskareli Museum advisor – Art and Fashion Historian Dictionary of less known terms: Openwork – a term used in the history of visual culture for techniques that produce decoration by openings in solid materials such as metal, wood, stone, pottery, ivory, leather, or cloth. Passementerie – the art of making trimmings or edgings, buttons, tassels, fringes, etc. Fragment of bobbin lace, Brussels, 1725–1750; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA); photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain Fragment of needle lace, Venice, 17th century; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC0 1.0 Jan Vermeer, The Lacemaker, around 1669–1670; The Louvre Museum, Paris; photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain After Claude Lefèbvre, Louis XIV, around 1670; Palace of Versailles, Versailles; photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain Tailor shop of Berta Alkalaj, Wedding dress with machine lace details, Belgrade, 1911; Museum of Applied Art, Belgrade; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

Mothers, fashion, and other stories

An interesting fashion exhibition titled M&Others, dedicated to the complex theme of fashion and motherhood, is open from June 14, 2024, to January 6, 2025, at the Fashion Museum in the Belgian city of Hasselt (Modemuseum Hasselt), which is just about an hour’s drive or train ride from Brussels. The occasion for the exhibition was the grand Marian celebration in honor of Hasselt’s patron saint, the Virgin Mary – the Jesse Tree (Virga Jesse), which was held from August 11 to 25, 2024. This celebration has been taking place in Hasselt every seven years for 340 years, with a painted, wooden Gothic statue of the Virgin Mary from the 14th century, kept in the local basilica, at its center. The inspiration fashion designers draw from faith, sacred art, and the Virgin Mary as the ideal woman and mother is evidenced by selected runway models displayed at the exhibition. Among them are models from Jean Paul Gaultier’s iconic spring collection for 2007 with striking quotes from Catholic visual art, as well as a model from the popular Dolce & Gabbana Tailored Mosaic collection for 2013, based on motifs from Byzantine-style mosaics in the cathedral of Monreale in Sicily. The exhibition, curated by Eve Demoen, traces the attitude towards the cultural identity of mothers, which has gained increasing importance in society and fashion since 1900. In addition to dresses and corsets from the 19th century, designed to conceal changes in the body of the expectant mother, the exhibition also features the cover of Vanity Fair magazine from August 1991, with a nude photograph of actress Demi Moore in her seventh month of pregnancy, taken by famous American photographer Annie Leibovitz. Starting from the cult of the Virgin Mary and European bourgeois culture, this dynamic exhibition reaches to contemporary fashion experiments and controversies with various social stereotypes related to the female body. After giving birth to her daughter Marguerite in 1895 at the age of thirty, fashion designer Jeanne Lanvin began designing children’s clothing. In 1908, she opened a children’s department in her fashion house, and in 1909, a department for mothers and daughters, where mothers could buy complementary clothing for themselves and their little girls. In recent decades, this concept of dressing mothers and daughters has been trending as Mini Me. On the other hand, the symbolic fashion mother Madeleine Vionnet is presented at the exhibition with a branching installation that shows her great influence on both contemporaries and fashion designers of future generations. In addition to creating new canons of female elegance by liberating the female body from corsets, Vionnet, whose fashion house operated intermittently from 1912 to 1940, gave her employees maternity leave and provided daycare for their children. Many famous fashion designers were influenced by the personality and style of their own mothers. Christian Dior kept a photograph of his mother Madeleine Dior on his desk, wearing a dress with a narrow waist, following the Belle Époque fashion. As a homage to Madeleine, the narrow waist became characteristic of Dior’s New Look, launched in 1947. Dior also found inspiration in memories of colors in the interior of his childhood home in Granville, Normandy, where the Christian Dior Museum (Musée Christian Dior) is now located, as well as in various types of flowers in the home garden that his mother carefully tended. The exhibition also showcases paper dolls for dressing that Yves Saint Laurent made at the age of 17, modeled after the fashionable clothes from his mother’s wardrobe. In numerous stories about mothers, maternal figures, and fashion, of which only a few are briefly told in this blog, classic Hermès bags Birkin and Kelly have also found their place. On a flight from Paris to London in 1984, actress Jane Birkin complained to Jean-Louis Dumas, president and artistic director of the Hermès fashion house, that she couldn’t find a bag that would meet all her needs as a mother. Dumas soon devised a solution in the form of a spacious, functional rectangular bag. This Hermès model, which even contained pockets for baby bottles, is now known as the Birkin. Another luxury Hermès bag, the Kelly, entered fashion history in 1956 when Grace Kelly, Princess of Monaco, tried to use it to conceal her pregnant belly from intrusive paparazzi. Draginja Maskareli Museum advisor – Art and Fashion Historian Dictionary of less familiar terms: Jesse Tree — a scene typical of Eastern and Western Christian art, depicting the body of the sleeping Jesse, father of the prophet David, from which a vine grows upward with figures of Jesse’s descendants and Christ’s ancestors on its branches, and at the very top, the Virgin Mary with Christ. With the words But a shoot shall sprout from the stump of Jesse, and from his roots a bud shall blossom (Isaiah 11:1), the prophet Isaiah foretold Christ’s birth in the Old Testament, which is why the Jesse Tree is also one of the names for the Virgin Mary. A well-known representation of the Jesse Tree is in the Visoki Dečani Monastery near Peć, created around 1338–1348. The Jesse Tree became a model for family trees. Virgin Mary – Tree of Jesse (Virga Jesse), 14th century; the basilica in Hasselt; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 / photo: Kris Van de Sande Exhibition M&Others, Modemuseum Hasselt, 10 September 2024; photo: D. Maskareli Exhibition M&Others, Modemuseum Hasselt, 10 September 2024; photo: D. Maskareli Exhibition M&Others, Modemuseum Hasselt, 10 September 2024; photo: D. Maskareli Exhibition M&Others, Modemuseum Hasselt, 10 September 2024; photo: D. Maskareli

Summer, Art and Fashion

For a long time, summer has been an inspiration both for fashion designers and other visual artists, while sunny, warm, and long summer days demand serious fashion preparations, regardless of whether we spend them at work or on vacation. Carefully selected, practical, and quality summer clothes will make us elegant and trendy during numerous and diverse summer activities, but also provide us with the feeling of comfort, confidence, and ease. As a season of travel, exploration, and new experiences, summer is a good occasion to look back at some of its iconic representations in art, which show the importance of fashion in the life of a modern individual. In his essay The Painter of Modern Life, published in the Figaro newspaper in 1863, poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire expressed the view that fashion is an important expression of modernity, criticizing contemporary artists for dressing their models in the clothes of the past. One of the artists influenced by Baudelaire is James Tissot, a painter, illustrator, and caricaturist known for his realistic portraits and genre scenes. During his upbringing, as the son of a textile merchant and a milliner, Tissot developed a sense for clothing details, to which he paid special attention. It is known that the artist had a rich assortment of dresses in the studio where he painted his sitters and that he represented the same dress multiple times. One of the recognizable garments in Tissot’s paintings is a white summer afternoon dress of muslin, decorated with ruffles and yellow bows, in line with the fashion of the 1870s. In the compositions Summer (1876), Officer and Ladies on the Deck of HMS Calcutta (c. 1876), and Spring (c. 1878), this dress is accompanied by appropriate fashion accessories such as a hat, parasol, or fan. In the second half of the 19th century, the Impressionist movement in art celebrated the beauty of the moment and everyday life. Summer and fashion often appear as themes in the works of the Impressionists. Claude Monet painted several summer genre scenes known as Woman with a Parasol. One of them is Woman with a Parasol – Madame Monet and Her Son (1875), which was painted in Argenteuil. The painting depicts Monet’s first wife Camille, walking with their son Jean on a windy summer day. In addition to the white summer dress, Camille wears a hat with a veil fluttering in the wind and an open green parasol, a common fashion accessory at the time. Following Monet’s example, the motif of an open parasol would later appear in the paintings of John Singer Sargent, a portraitist who used clothing as a powerful tool for expressing personality and identity in visual art. In the famous painting Luncheon of the Boating Party (1880–1881), Pierre-Auguste Renoir depicted a group of his friends, members of Parisian high society. An important part of this scene, set on the banks of the Seine, on the terrace of the Maison Fournaise restaurant near Paris, is the various male and female, formal and informal clothing: classic men’s suits with top hats and bowler hats, sportswear with straw hats, as well as modern women’s clothing – dresses with ruffles and lace worn with fanciful hats decorated with flowers and ribbons. Among the personalities depicted in the painting is Aline Charigot, a seamstress, Renoir’s model, and future wife, sitting at the table with her dog in the lower left corner. Besides Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party, one of the most popular representations of summer and fashion in art is Georges Seurat’s painting A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884). This Neo-Impressionist painting was done using the technique of Pointillism, which involves applying colors to the painting surface in short strokes (dots) to create the illusion of whole forms in the viewer’s eye. Among the clothing of various layers of Parisian society in the park on the island of La Grande Jatte, women’s clothing from the bustle fashion period, which lasted during the 1870s and 1880s, attracts special attention. The striking bustle silhouette, with support structures that expand the rear part of the skirt, gives Seurat’s complex painting the quality of an interesting fashion testimony. Draginja Maskareli Museum advisor – Art and Fashion Historian James Tissot, Summer, 1876; photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain / Tate Britain James Tissot, Spring, 1878; photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain Claude Monet, Woman with a Parasol – Madame Monet and Her Son, 1875; photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain / National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party, 1880–1881; photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain / The Phillips Collection Georges Seurat, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884; photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain / Art Institute of Chicago

Medal-worthy style: a brief history of Olympic fashion

From July 26 to August 11, 2024, Paris, one of the world’s fashion, art, and style capitals, will host the Olympic Games for the third time. At this major international sporting event, which brings together athletes, audiences, numerous staff, officials, and media teams, the distinctive Olympic uniforms are an important part of the visual identity. Beyond their primary function of providing comfort, mobility, and protection, the uniforms serve as a means of visual communication, marking not only national identity but also the roles of different participants in the protocol and competitive aspects of the Games. They also reflect current trends in the sportswear industry, moral codes of the time, budget constraints, and various national branding strategies. In the early Olympic Games, participants wore their own sports equipment and clothing, which led to the introduction of clothing in specific colors and markings such as badges or armbands for easier identification. The development of ceremonial practices directly influenced the design of Olympic uniforms. At the opening of the London 1908 Olympics, the Parade of Nations, a march of national teams, was held for the first time, becoming one of the most recognizable Olympic traditions. At the Parade of Nations in Paris in 1924, many participants appeared in national uniforms, contributing to the visual dynamism of this event, which has since become a kind of visual and fashion spectacle. With the strengthening of media influence after World War II, various authors began writing the history of Olympic fashion. One of them was French fashion designer André Courrèges, who designed the uniforms for the staff of the 1972 Munich Olympics. To distance themselves from the 1936 Berlin Olympics, held under the shadow of the Nazi regime, the organizers wanted to give the Munich event a relaxed and informal character. They required that the uniforms be inspired by Bavarian folklore and safari style, with a defined color palette that included light blue, green, lavender, orange, and silver gray. Considering these guidelines, Courrèges designed practical clothing that included overalls, baseball caps, miniskirts, and jackets. This clothing is also remembered because it was worn by the future Queen Silvia of Sweden, who met her husband, then Crown Prince and now King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden, as a hostess in Munich. Among the designers of Olympic uniforms over time have been names like Ralph Lauren, Giorgio Armani, Issey Miyake, and Christian Louboutin. For the London 2012 Olympics, Stella McCartney designed the entire Olympic collection for the Great Britain team. On that occasion, she stated that the competitive uniforms were a bigger challenge for her than the ceremonial ones. The deconstructed Union Jack motif she used in 2012 was criticized for being too blue. Therefore, for the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics, she chose a heraldic design with floral emblems of the four British nations, the Latin motto Ivncti in Uno (Joined in One), and the GB logo. Besides comfort and practicality, Stella McCartney’s Olympic uniforms are characterized by bold graphic prints, colors, and inspiration from British heritage. Presentations of the Olympic uniforms of participating countries’ teams traditionally attract attention in the weeks leading up to the opening of the Games. At the 2024 Paris Olympics, the French team will appear at the Parade of Nations in uniforms by the brand Berluti. The design of these dark blue suits, modern versions of tuxedos, embodies elegance and sophistication as synonyms for the host country’s style. Serbian Olympians will defend their national colors in Paris in uniforms by the brand PEAK. The design of the Olympic collection for Team Serbia is based on the colors of the national flag – red, blue, and white – but also on symbols, notably the cross as a universal symbol of faith, hope, love, and victory. Draginja Maskareli Museum advisor – Art and Fashion Historian Poster for the fencing events at the 1900 World Fair and Summer Olympics in Paris; photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain U.S. Olympic swimming team at the Paris Olympics 1924; photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain Clothes of the volunteers at the Munich Olympics 1972; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 1.0 / User: H-stt Parade of Nations at the London Olympics 2012; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0 / Department for Culture, Media and Sport Athletes from Serbia at the opening of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0 / Jude Freeman

Fashion, Identity, and Culture of Living in Belgrade in the 19th and Early 20th Century: Religious Holidays and Balls

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, religious holidays were an important segment of social life and identity in Belgrade. The celebration of religious holidays was an important event in the family, so the house was thoroughly cleaned before each holiday, and numerous traditional dishes and cakes were prepared. Serbian slava is one of the elements included in the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Slava, as a solemn celebration of the family’s patron saint, besides the religious one, also had a strong social component, which included the exchange of visits. On days of great feasts, such as St. Nicholas, on the streets of Belgrade, solemnly dressed married couples could be seen, who visited the acquaintances on foot or by carriage. Men wore a black suit, black coat, hat, or top hat, while women wore visiting dresses, usually of darker colors, with some discreet jewelry and a mandatory hat. The drawing of the Austro-Hungarian travel writer Felix Kanitz from 1859 represents the slava of a Belgrade family. Members of the family, dressed in national costume, are shown welcoming guests in an interior the appearance of which is fully harmonized with the cultural model of bourgeois Europe. Although the European fashion influence has prevailed in Belgrade since the middle of the 19th century, the national costume, as clothing with appropriate symbolism, was still worn at slavas and other special occasions. Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, and Easter were celebrated mostly in the family circle. The people only went to church or to visit the elders and greet them. Lawyer and politician Kosta Hristić notes in his memoirs that on Good Friday, a solemn ritual of bringing out the Epitaphios is performed in all churches, while it is especially solemn in the Cathedral. A special place in the children’s calendar of holidays was occupied by Lazarus Saturday or Vrbica, which was also an occasion to buy children new festive clothes for the holiday procession. On that occasion, girls wore silk dresses, hats, and patent leather shoes, while boys wore popular sailor suits and sailor caps. Hristić also remembers small merchants who decorate their windows with whole wreaths of small Vrbica bells, children’s caps, dresses, and straw hats, but also the big ones, with fashionable goods in new styles, felt and Panama hats, all of the latest form and color. During the ball season, which lasted from December to the end of March or the beginning of April, numerous balls were held in Belgrade. The balls were organized by different associations, including the Women’s Society, Officer Corps of the Belgrade Garrison, Belgrade Singing Society, Belgrade Shooting Society, Craft Association, Belgrade Trade Youth, and Belgrade Workers’ Society. Balls were often held in the Civil Casina, which was founded in 1869 and located in the Main Bazaar, at the corner of today’s Kralja Petra and Kneza Mihaila streets. The establishment had great importance for the development of social life in Belgrade. In addition to balls, there were also held concerts, speeches, parties, and art exhibitions, while the Civil Casina reading room had a well-stocked library, and regularly received local and foreign newspapers and magazines. The most solemn were the court balls attended by high-ranking military figures, politicians, diplomats, and distinguished merchants with their families. Kosta Hristić left a written testimony about one of the balls held by Prince Mihailo and Princess Julija. This ball was attended by guests from all levels of society: merchants in European or “Turkish” dress, women in Serbian dress with caps – tepeluks, belts – bajaders tassels, and necklaces of pearls and ducats, young women and girls in broad crinolines, but also people in Turkish and Austrian uniforms, such as the Belgrade pasha and senior Austrian officers from Zemun and Pančevo. Court balls were particularly glamorous in the 1880s, during the duration of the marriage of King Milan Obrenović and Queen Natalija, as well as during Natalija’s stay in Serbia as Queen Mother in the mid-1890s. At court balls, in addition to the ball dress, the national costume often appeared as a dress code for women. Particularly popular were the so-called costume balls where, instead of ball dresses, various folk and exotic costumes were worn. Draginja Maskareli Museum advisor – Art and Fashion Historian Dictionary of less known terms: Epitaphios – a religious textile with embroidered or painted images showing the body of Christ immediately after being taken down from the cross Tepeluk (tr. tepelik) – a shallow women’s cap made of red cloth and decorated with pearl embroidery, worn as a part of Serbian national costume Bajader – a long and wide patterned silk sash with fringes, worn as a part of Serbian national costume Slava-celebrating family, Belgrade, 1859; source: Kanic, F. (1989), Srbija : zemlja i stanovništvo od rimskog doba do kraja XIX veka, prva knjiga, Beograd, Srpska književna zadruga. Walking and visiting dress; Nedelja, Belgrade, 21 February 1910 Spring children’s dress; Nedelja, Belgrade, 7 February 1910 Walking dress for grown-up girls; Nedelja, Belgrade, 14 February 1910 Modern ball dress and newest spring dress, style “Directoire”; Nedelja, Belgrade, 21 February 1910

Fashion, Identity, and Lifestyle in Belgrade in the 19th and Early 20th Century: Gatherings, Sports, Recreation, and Excursions

Social life in Belgrade developed intensely during the 19th century. A popular form of the social gathering was a women’s salon – poselo, which had been held since the late 1830s. The first women’s salons were organized by Marija Milutinović, known as Maca Punktatorka, the wife of the poet Sima Milutinović – Sarajlija, and later by Anka Konstantinović, the daughter of Prince Miloš’s brother Jevrem Obrenović. At these gatherings, various women’s topics were discussed, with fashion occupying an important place. Additionally, the women were introduced to European culture, advised on child-rearing and home decoration, and various daily events were discussed. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such gatherings became known as jours. This term originated from the French term jour fixe, which denoted a fixed day of the week when the hostess would receive her friends. Various sports activities also became an indispensable part of life in Belgrade. On the city’s streets, especially on the Promenade in Kneza Miloša Street, men and women could be seen riding horses recreationally. Among the first women to engage in this sport were the daughters of Prince Aleksandar Karađorđević. They rode on side-saddles, wearing half-cylinders on their heads and boots. The first horse races in Belgrade were organized in 1863 by Prince Mihailo Obrenović, who was an excellent rider and a great lover of equestrian sports. In Belgrade, fencing and shooting, as well as gymnastics and martial arts, also developed. The fencing society Srpski mač (Serbian Sword) was founded in 1897, and in 1906, the football club of the same name was established. The football club Soko (Falcon) was founded in 1903, and BSK (Belgrade Sports Club) in 1911, while the First Serbian Society for Gymnastics and Wrestling was established as early as 1857 by painter Steva Todorović. In the last decades of the 19th century, recreational sports such as cycling, ice skating, tennis, and swimming emerged. The First Serbian Bicycle Association was founded in 1884. This association also had its ice rink, located where the Central Military Club of Serbia stands today. A reporter from the newspaper Politika noted in January 1905 at the ice rink of the First Serbian Bicycle Association that male and female skaters were not dressed as they should be, recommending cycling attire for men and the shortest possible skirts for women, mentioning that this was not shameful since in America and England, women already wore such skirts on the streets, and no one laughed at them. During the summer months, excursions were an important part of city life. Wealthier citizens temporarily moved to their summer houses in Topčider or traveled to some resort or spa, while excursions to the city’s surroundings were a pleasant summer pastime available to the wider population. Popular excursion spots around Belgrade were Topčider and Košutnjak. The Austro-Hungarian travel writer Felix Kanitz recorded that especially on Sundays and holidays, /…/ the shady paths leading from the railway station to the restaurants were covered with crowds of cheerful people and that people preferred to stop in the wooded corner around Hajdučka Česma. Excursions were an opportunity not only to rest from daily obligations but also for more casual attire, suited to outdoor activities. In a group photograph of excursionists in the vicinity of Belgrade, from the collection of the Museum of Applied Art, taken around 1900 by the famous photographer Milan Jovanović, a rich assortment of various men’s and women’s hats is documented. While women, following the fashion of the time, wore striking and decorated hats, on the men’s heads we can see almost all types of men’s headgear typical for the 19th and early 20th century: fez, top hat, bowler hat, homburg, fedora, boater, and caps worn as part of a uniform. Although the lawyer and politician Dimitrije Marinković noted in his memoirs that in the mid-19th century, the fez was not considered unusual, while men’s hats at that time, and later, were very rare, by the beginning of the 20th century, the hat had become an indispensable detail in men’s attire.* Draginja Maskareli Museum advisor – Art and Fashion Historian * For the accompanying photos, which testify to the past life in Belgrade, we owe special thanks to Miloš Jurišić. Dictionary of less familiar terms: Homburg hat – a semi-formal felt hat, with a single dent running down the center of the crown, a silk ribbon, and a flat brim shaped in a pencil curl, with a ribbon trim around the edge. It was named after Bad Homburg in Hesse, where it originated as a hunting hat type. Fedora – a felt hat with a soft brim and a crown typically dented lengthwise and pinched near the front on both sides. A famous fedora manufacturer is the Italian brand Borsalino. Boater – a stiff straw hat with a flat brim, a shallow, flat crown, and a silk ribbon. Skating rink of the First Serbian Cycling Association, 1900s; photo: the collection of Miloš Jurišić Cyclist, 1900s; photo: the collection of Miloš Jurišić People on a side trip in Košutnjak, Belgrade, 1913; photo: the collection of Miloš Jurišić People on a side trip on the lake in Kijevo, Belgrade, 1909; photo: the collection of Miloš Jurišić Milan Jovanović, Group portrait of people on a side trip, Beograd, oko 1900; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 RS DEED / Museum of Applied Art in Belgrade / user: Gmihail

Women’s Urban Dress and National Costume in Serbia in the 19th Century

During the first decades of the 19th century, the appearance of urban dress in Serbia was fully harmonized with the Ottoman-Balkan cultural model and the shared visual culture of the inhabitants of Ottoman cities. In the book Putešestvije po Serbiji (Travels in Serbia), Joakim Vujić described in detail the dress of the urban population, that he saw during his visit to Belgrade in 1826. In the illustration of Grigorije H. J. Vujić in the same book, you can see men’s, women’s, and children’s clothing, significantly different from what we recognize today as the Serbian urban dress and national costume of the 19th century. The dominant element of this dress pattern is the anterija (Turkish: entari), a distinctive long dress open in the front, which was worn both by men and women throughout the Ottoman Empire over wide, baggy trousers – dimije (Turkish: şalvar). After the end of the uprising period, and especially after gaining autonomy in 1830, the pluralism of cultural models came to the fore in the Principality of Serbia. At that time, the national costume was created by selecting characteristic garments from the dress inventory of the urban population, living in formerly Ottoman cities. The process unfolded parallelly with the establishment of the European fashion system and the new bourgeois elite perceived the constructed national costume as authentically national dress, which is why it was often used in family portraits as a visual marker of identity. Family portraits were gradually introduced into Serbian bourgeois culture from the end of the 18th century in the Habsburg Monarchy while the citizens of the Principality of Serbia adopted the practice of owning family portraits at the beginning of the 19th century, adapting their iconography to the needs and ideas of their own milieu. In public and private collections, numerous portraits have been preserved to this day, which were an indispensable part of the urban interior, and emphasized the social status of the persons depicted. The basic variant of the women’s national costume consisted of a fistan – a long dress, cut at the waist, with a characteristic heart-shaped neckline, then a shirt, a scarf to cover the chest, a bayader – a wide, patterned silk belt, libade – a short jacket with wide sleeves, as well as a headdress – fez and tepeluk. As a newly formed dress of the elite social class and a costume type imprinted with a national character, it appears in the official portraits of Princesses Ljubica Obrenović and Persida Karađorđević. Speaking about Princess Ljubica’s dress, the German travel writer Otto Dubislav Pirch stated in 1829 that it can be even plainer than that of other urban women, the only difference being beautiful sable fur and a brilliant in her hair. British admiral Adolphus Slade says that during the meeting, in 1838, the princess was dressed in the Greek style, in a fur jacket, cloak, and with a turban on her head. The brilliant in her hair particularly stood out as part of the headdress of Princess Persida’s rich urban dress. The large and expensive brooch of flower bouquet – grana, which decorated her headband – bareš, resembled a diadem. The richness of the princess’s costume is also shown by her portrait from the collection of the National Museum of Serbia, the work of Katarina Ivanović from 1846–1847. In the visual representation of members of Serbian ruling and bourgeois families, we often find elements of the national costume combined with modern clothing. In the official portrait, painted around 1865, Princess Julija Obrenović is shown, in accordance with current European fashion trends, in a dress with crinoline, with which she wears libade and tepeluk. Also, in 1881, Carl Goebel painted Princess Natalija Obrenović, dressed in a luxurious dress with a bustle, combined with parts of the national costume. The first portrait is kept today in the National Museum of Serbia, and the second in the Museum of the City of Belgrade. It is common for family photos from the last decades of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century to show married couples dressed in such a way that the woman wears a variation of the national costume while the man wears a modern men’s suit. From the traditional elements of the national costume, which were worn in combination with modern dresses of European cut, the libade and tepeluk persisted the longest in the women’s clothing inventory. The French Slavic scholar Louis Léger recorded in 1873 that the embroidery on the libade and the pearl on the fez [tepeluk] were left […] until now as a legacy to the female members of the family and they passed from the mother’s wardrobe to the daughter’s outfit. Léger also states that he saw people wearing pearls worth one hundred ducats on their fez. Draginja Maskareli Museum advisor – Art and Fashion Historian Pavle Vasić, Men’s and women’s dress in Belgrade, after Grigorije H. J. Vujić; photo: private owner/author’s archives Jacket – libade, National Museum Kruševac; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED / National Museum Kruševac / user: Ioannes2909 Cap – tepeluk and headband – bareš, the second half of the 19th century, Museum of Applied Art, Belgrade; photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED / Museum of Applied Art in Belgrade Uroš Knežević, Princess Ljubica Obrenović, before 1855, National Museum of Serbia; photo: Wikimedia Commons / public domain Katarina Ivanović, Princess Persida Karađorđević, 1846–1847, National Museum of Serbia; photo: Wikimedia Commons / public domain